Animation Edition

This monsoon, three of our writers rain down their favourite animated films on you. Hallelujah!

ATTENTION!!!

After the beginning of Israel’s war on Gaza, Israel started bombing it from the north moving down, displacing millions of Palestinians who were ushered into Rafah to seek shelter. By February, about half of Gaza’s 2.3 million population had been pushed into Rafah.

On the night of May 26th, two days after the International Court of Justice ordered Israel to halt its offensive in Rafah, Israeli bombardment killed forty-five people in al-Mawasi in western Rafah, which was previously declared a safe zone. The Gaza Government Media Office said Israel dropped seven 900 kg bombs as well as missiles on the displacement camp. Many shelters burst into flames with their occupants still inside. Displaced Palestinians were forced to dig through smouldering remains with their bare hands – looking for bodies, or injured people, or in some cases, a few scraps of food they could salvage to keep their families going a bit longer. Horrific videos emerged of the aftermath – the most notable was of a man holding up the corpse of a young child without a head.

(Source: Al Jazeera)

While the governments of the world may or may not strive to hold Israel accountable, the countless victims of this massacre require our help. Here is a list of verified donation links to relief funds. At CUT, AND PRINT!, we stand in solidarity with the humanitarian efforts of the funds listed below and urge our readers to consider donating.

UN Relief and Works Agency - https://donate.unrwa.org/-landing-page/en_EN

United Nations Population Fund - https://rb.gy/rv2ov0

WHO Foundation - https://rb.gy/uww4wu

Save The Children - https://www.savethechildren.org/us/where-we-work/west-bank-gaza

Human Concern International - https://rb.gy/rinrpq

MATW Project - https://rb.gy/h6kin0

Human Appeal - https://rb.gy/liur8t

INTRODUCTION

Hey June, don't make it bad.

Take our reflections on animations and make it into a special issue newsletter!

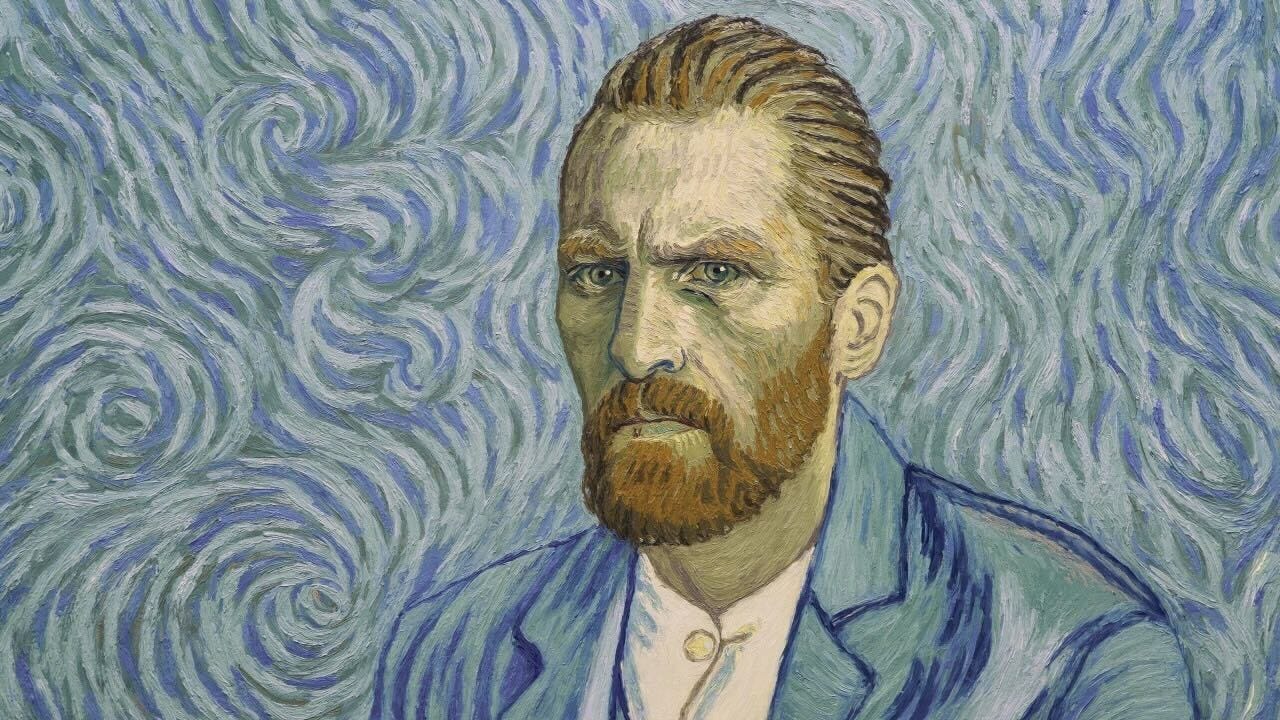

One for Fun Times, Prakhar Patidar revisits Disney’s experimental anthology Fantasia (1940), framing it as a feel-good psychedelic experience. In The Adventures of Tintin (2011), Varun Oak-Bhakay draws in on his perfectly married twin loves – literature and cinema. Through Loving Vincent (2017), Mahika Kandalgaonkar brushes upon the life and legacy of Vincent Van Gogh.

Read it monsooner than monlater!

I. Fantasia (1940)

PRAKHAR PATIDAR

I have always been a little afraid of “house-partying” too hard with the purist cinephiles. Somehow, one finds oneself cornered into a conversation about classics. Should you find yourself in such a scenario, and the gathering has succumbed to a game of “Never Have I Ever”, throw integrity out the window and just take a sip when one chimes in the following confession:

Never have I ever watched [insert a classic, preferably by someone from the house of auteurs]

Then pray someone else hasn’t watched it and sit back for the sales pitches to roll in.

If intoxication and conversation must steer to classics in a bid to elevate the high when dulled senses seek visual simulation so the brain can feel happy again, then my question is why did no one ever bring up Disney’s wonderful animation experiment: Fantasia (1940)?

This ambitious anthology is classical music interpreted into animated shorts. The celebrated American composer Deems Taylor narrates in live action and Leopold Stokowski conducts the Philadelphia Orchestra to perform music that is visualised on screen by Walt Disney and the team. The result is each moment on screen choreographed to each note you hear begging the question – How do we see music? How do we imagine it?

Have you ever given it a thought? Of course, there’s the cannon event of imagining oneself in music videos on car rides – the rainier the day, the longer the ride, the better. What Fantasia, when viewed as hopefully in the years post a fully developed brain, demands is that you don’t imagine images accompanied by the said music but imagine a look for the music itself. The first of the animated shorts is Bach’s eighteenth-century composition Toccata and Fugue rendered into abstract shapes and movements that are oddly satisfying to watch. As these abstractions take shape, form and narrative over the next few segments, you find yourself amidst fairies, forests, dancing mushrooms, Mickey Mouse with a personified broom, Earth’s evolution, Greek myths, a ballet performance by various animals, and good-old good versus evil showdown.

Very few things have managed to capture the essence of waves in all its forms – from the soft sways to raging roars. My list of these things includes being in the car with a friend who is scarily good at driving and carelessly smug with it, landline phone conversations after school in 2013, a woman’s emotions in the week before periods, grief, and, most importantly, music. Fantasia takes it upon itself to bring one temporal artform – music – with another – moving image – and explores this feeling of what we viscerally understand as “flow”. The fact that the image we see moving to music is animated brings the film closer to an apt imagination of “flowing”. This is best achieved by the second segment of the film: “The Nutcracker Suite” by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. If live action’s magic lies in capturing the ephemerality of life, closing in or out, baring what the eye is incapable of seeing, animation excels in creating impossibly satiny movements. Sound is the unsung hero for why animation feels like running your hand over a piece of satin. Fantasia is a testament to that.

The third segment – “The Sorcerer's Apprentice” by Paul Dukas – is most narrative-driven and the weakest of all. It is more a derivative of the musical piece’s title than the music itself. A cautionary tale about an apprentice Mickey finding magical shortcuts to get out of tasks left for him by the sorcerer offers nothing more than other Mickey Mouse cartoons of the time. But what immediately follows, the fourth segment – “Rite of Spring” by Igor Stravinsky – arguably the best of the film, is worth all the attention. Evolution is in itself a theme that never fails to intrigue but to watch the segment with the knowledge that this film was made in 1940 (!) adds another layer of awe to it. If there’s another thematic element that you can’t go wrong with after evolution, it is dinosaurs. The sheer display of cinematic craft in this single segment makes up for the disappointment of Mickey and its backstabbing broom.

The fifth segment: “The Pastoral Symphony” by Ludwig van Beethoven, is played to the myth of Dionysus, his giddy winemaking, merriment and feud with Zeus. Up until this point, one may feel the “fun times” reading of the film is a silly lens, but this segment is as clear as the signifiers can get. What follows is an endearingly bizarre ballet performance of “Dance of the Hours” by Amilcare Ponchielli and a fittingly climactic tale of Chernabog, accompanied by “Night on Bald Mountain” by Modest Mussorgsky and “Ave Maria” by Franz Schubert. Chernabog is a Slavic mythic character, the god of darkness, who is caught in an eternal conflict with Belabog; the god of light. I call this conclusion choice fitting because what else is after hours for if not diving deep and encountering the eternal struggles of the soul at 3 AM?

I can’t confirm what a good psychedelic trip looks like, but it sure feels like Fantasia. This one is for dulled senses and altered states of mind.

II. The Adventures of Tintin (2011)

VARUN OAK-BHAKAY

I first encountered the boyish-looking Belgian reporter and his fluffy white dog in the mid-oughties when my sister and I accompanied our parents to a Crossword outlet one summer afternoon. This wasn’t by any means a remarkable outing: bookstore visits were a must during vacations, given we lived in a town which didn’t have one we knew of. Our father had the enviable task of acquiring some books for the Division Library and among the chosen few was the hefty collected set of Hergé’s comics. Much as we (and he) wanted to, the books remained sealed throughout the holidays and were promptly dropped off at the library the moment we were back from vacation.

About half a decade later, out of the blue, our father announced that we’d be spending an evening reveling in The Adventures of Tintin at Sathyam Cinemas. It was the first Hollywood production to make its India bow before opening stateside, a move distributor Sony attributed to the character and the comics’ enduring popularity in the country, which likely outstripped the appeal it held for US audiences.

I recall being blown away by it, a rarity for me with 3D films. It felt doubly familiar: not only was I acquainted with the character but the film itself felt stylistically very similar to the event-a-beat rhythm a lot of mainstream Hindi cinema, on which I grew up, was about.

Watching it for a third time allowed me to soak in the film without any distractions. I could revel in the play of light that Steven Spielberg achieved in a fashion like live action cinema. The ambivalence around Tintin’s age, a difficult quirk to retain outside the animated realm, worked wonders. He was an intrepid reporter but did look, as Captain Haddock suggested, a bit like a “baby-faced assassin”. And in combining as many as three albums, Spielberg, producer Peter Jackson, and writers Edgar Wright, Joe Cornish, and Steven Moffat found a single narrative thread that also served as an introduction to Tintin.

There is plenty of masala entertainment within Spielberg’s cinema, mostly in the Indiana Jones films but also in something like Catch Me If You Can [2002]. In Tintin, he embraces the pomp and show that is inherent to the style, be it the slickness of the narrative thrust or the playfulness of the events. The film feels a sumptuous bit of street food where one can taste the many elements – from the tang of the imli chatni to the crunch of the paapdi – and marvel at them but also just enjoy the whole without necessarily being distracted by the surreal flicker of light that would be unimaginable in traditional animation but which is the hallmark of something like Tintin.

It might seem like a backhanded compliment but the truth is that Tintin doesn’t feel much like an animated film. Of course, the camera moves around and actual actors drive the performances (barring Snowy’s), which are basic functions of performance capture animation, but the rendering of every object and face comes eerily close to real-life human interaction. And that perhaps is Tintin’s most significant achievement: in much the same vein as films like King Kong [Peter Jackson, 2005] and Rise of the Planet of the Apes [Rupert Wyatt, 2011], it draws open the curtain between animation and live action and demonstrates just how far animation could go.

III. Loving Vincent (2017)

MAHIKA KANDALGAONKAR

‘You want to know so much about his death, but what do you know of his life?’ Marguerite asks Armand when he seeks answers about Van Gogh’s death. Filmmakers Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman pose the same question throughout Loving Vincent. Armand’s simple task of delivering a letter turns into a quest for the truth as he uncovers more about the life of Van Gogh – the tortured artist – who is believed to have shot himself. Marguerite further tells Armand ‘No detail of life was too small or too humble for him. He appreciated and loved it all.’ This mindset informs Van Gogh’s bold use of colour and dramatic brushwork in his paintings, and it also stands out as a prominent visual theme in the film.

Dr. Gachet hands Armand a letter written by Van Gogh to his brother when he was embarking on his journey as an artist. It reads: ‘Who am I in the eyes of most people? A nobody, a non-entity, an unpleasant person. Someone who has not, and never will have any position in society. In short, the lowest of the low. Well then even if that were all absolutely true, then one day I will have to show by my work what this nobody, this non-entity has in his heart.’ No wonder Van Gogh significantly influenced the rise of expressionism in modern art as it is an art form from a subjective perspective that uses distortion to express moods far away from reality.

Similar to Van Gogh’s paintings, the creators of Loving Vincent too tried to throw aside the traditions of the past and in the spirit of experimentation made it the first fully painted animated feature film. In doing so, the film paid homage to the father of modern art by involving over a hundred artists from around the world, who meticulously hand-painted each of the film's frames in a form resembling rotoscoping (tracing live-action images) by not only using the same techniques as Van Gogh but also incorporating his paintings into scene backgrounds and thereby evoking the same emotional impact as his original artwork.

The film discusses Van Gogh’s previous professional encounters as dead ends. David Epstein, the author of the book “Range” about generalists triumphing in a specialised world, challenges the above belief stating that Van Gogh was “set free” by his failure to pursue work that better matched his talents and interests. The author also debunks the myth that Van Gogh died in anonymity emphasising that an ecstatic review cast him as a revolutionary months before he died, and made him the talk of Paris.

In her SXSW talk, psychotherapist Esther Perel says,

‘Americans think that every problem needs to have a solution and I don’t have a solution because many of these things are not a problem that we have to solve but these are paradoxes that we need to manage.’

Similarly, the film depicts the complexities of Van Gogh’s death without yielding simple good-and-bad or black-and-white answers but instead portrays the intricate life of a complex man woven by a narrative that is inspired by the characters and places in his paintings.

Picks of the Month

A short list of the writers each choosing the best film/show they’ve watched in the preceding month (1st May onwards).

1. Prakhar: May December (Todd Haynes, 2023)

2. Varun: The Fall Guy (David Leitch, 2024)

3. Mahika: Manjummel Boys (Chidambaram S. Poduval, 2024)

If you liked this issue and would like to keep up with what goes on Cut, and Print!, click/tap the button below. Don’t cry, we’ll see you in July!