#14

INTRODUCTION

A slightly delayed June release thanks to summer susti on the part of the one person of the three-member team who lives in the Western Hemisphere but we’re here and that’s really what matters. In this edition, Vanij looks at captor/captive relationships through the films Sebastiane and Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine; Prakhar examines fatherhood and the perspective of a child looking at their parent through Aftersun; and Varun revels in the discomfort cinema can often create in the viewer, and the perverseness of enjoying the discomfort in Shame.

1. Sebastiane & Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine: Captor/Captive Relationships and the Many Saints of Cinema

VANIJ CHOKSI

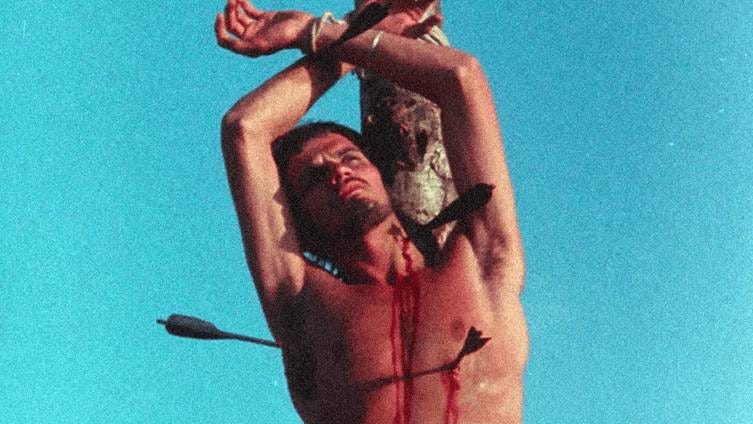

Derek Jarman’s gay gladiator film Sebastiane filmed, audaciously, exclusively in Latin, on site in Sardinia, and populated with men running around in nothing but thinly clad briefs – ‘We couldn’t afford costumes,’ Jarman jests – manages, as an addition to a long tradition of the iconic depiction of the execution of Saint Sebastian in Renaissance art, to hyperbolise its predominant usage in the context of Jarman’s pain as a homosexual individual within an essentialist heterosexual framework. Set amidst the casual homosexual encounters between the camped, quasi-exiled Roman soldiers, the eclectic Sebastian, devoted to the service of his God (though he identifies himself as a Christian, what form his God takes is uncertain), spurns General Severus’ perverse, erotic advances to have some authority over his body. Subjected, as a result, to severe punishment and torment, Sebastian experiences an erotic delight in his sufferance and resistance being tied under the scorching sun, receiving kisses from his God – pleasure and suffering seem to go hand in hand. Eventually, then tied to a post and penetrated with arrows by the often homophobic soldiers of the camp, Sebastian, as in most iconic depictions of his captivity, is shown with his head tilted in an upward gaze towards God.

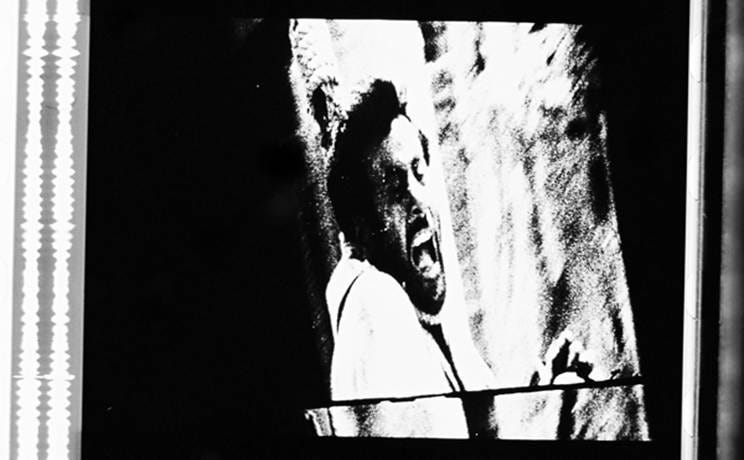

Found-footage filmmaker Peter Tscherkassky’s 2005 film Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine reinterprets Sergio Leone’s The Good, The Bad and The Ugly as an odyssey of Tuco (The Ugly), similarly enduring torment but contrasted to Sebastian’s pleasure, experiencing a severe identity crisis. Tscherkassky himself puts it, “[The film] is an attempt to transform a Roman Western into a Greek tragedy.” Becoming a sentient being and realising his position as a character in a film, Tuco attempts to escape his captivity. Instructions opens, in Tscherkassky’s classic style of revealing the film material’s artifice, with the negative image of an individual (the surrogate for us, the audience) passively watching Tuco’s journey from afar as he engages in a Western shootout, is tortured, experiences a filmic death and is finally dragged into Hades, the realm of shadows, where he paces from grave to grave attempting to escape his fate. Ideologically, Instructions explains how Tuco lies at the mercy of the filmmaker (the film world’s God) – his captor and tormentor – and most interestingly, to the film material itself. Consider every film that we watch as a literal prison for the subjects captured within it, consigned to a ritualistic captivity, an almost Sisyphean fate of living and dying over and over again for us, yet as viewers we have evolved to have a coolness of gaze, far removed and mostly passive in our contemporary tradition of film watching. The degeneracy of cinema into content, perpetuating a decay in our visual culture, elides the suffering of the martyrs and saints of cinema and further queering a relation to our own sufferings. Interestingly, the first instance of an assault on Tuco comes in the form of a classic Western shootout, a scene whose iterations have become quintessential to popular movies, such that it itself has been shot to death. Perhaps reflecting our evolved passivity as viewers, the effects of gory bloodshed logged firmly within the canon of mainstream cinema has lost all empathetic meaning, serving essentially pornographic purposes.

For Sebastian, pain and lust go hand in hand, resisting the eroticism of Severus as captor yet embracing with pleasure the suffering imposed upon him. We witness sexuality as much as we witness pain. Pain and suffering receive erotic and ennobling statuses, while returning the sexual expectations of a captor is likened more to a kind of suffering itself. The captor that Sebastian willingly serves is elusive and vague. He submits his existence to the embrace of a God whose presence is felt in His silence and the pain that is experienced from Sebastian’s torment. His endurance of torment is like an act of faith, of confirmation of belief and of sexuality itself. Exploring and exercising identity in resistance, Sebastian’s suffering achieves transcendental proportions. For Jarman, the pleasure he must receive in making his work is linked to Sebastian’s suffering and resistance. If the concepts of Instructions can be applied here, Sebastian becomes Jarman’s captive as well, and so he must suffer, as he once did in history, on film over and over again. But Jarman’s politics of desire aren’t as immediate and perverse as that of Severus’. Although Jarman too becomes a silent and far-removed captor, consigning Sebastian to his filmic Sisyphean fate, Tercan informs us, “the concept of pain directly used for the saint, and the director, as an LGBTI figure, implies the pain and process of social existence.” Therefore, in the use of film, Jarman, himself a captive to the dominant heterosexual hegemony of his time, finds and creates a feeling of pleasure in suffering and resistance from those who demand and desire your body for their pleasure or prerogative, erotically or otherwise. Jarman, as captor, manages to align Sebastian’s pains to his such that there exists a state of pleasure in sufferance and captivity while there exists at the same time the resistance of a captor. There is a perverse satisfaction of Sebastian-like proportions in expressing identity, particularly in the face of its repression. In a sense, the position of the captor as that of repressor of a certain otherness inadvertently validates the existence of that otherness itself, paving the way for its expression in its repression and suffering. As David, a Letterboxd user, puts it, ‘Even in my own personal experience, I’ve felt pangs of melancholy when I feel compelled to acknowledge that my now-quite-ordinary homosexuality no longer seems a valid credential to gain admission into the contemporary domains of radical “queerness”.’ Now that my husband and I have celebrated a decade of culturally and legally sanctioned [homosexual] normalcy, there’s still a part of me that craves the perverse satisfaction of playing Sebastian to the red state advocates of Severus-style severity.” Perhaps from Jarman’s personal experience, he is able to delineate a diagram of the positions held within a homosocial/homosexual continuum by including relationships and characters such as the homosexual normalcy of Anthony and Adrian and the often homophobic bully Maximus, who is eager to arrow Sebastian to death. Jarman’s exploitation of Sebastian for aesthetic purposes creates catharsis and expands on his resistance, transforming the almost pornographic content of the Sebastian icon and extending it to its most artistic and poetic extremes. ‘The old school Freudian term for this psycho-social alchemy is sublimation,’ David describes, ‘the cleaving off of part of the libido from its erotic objectives and its redirection onto “higher” acts of aesthetic creation.’

In Tuco’s case, Tscherkassky depicts an image of a captor that is somewhat well-defined, drawing similarities quite literally amongst the filmmaker, the audience and the film material. There is a moment in the film, right before Tuco’s descent into Hades, when he is hanged at the gallows. As Tuco oscillates on the chord, the film pendulums from left to right, literally and figuratively binding him in death and milking the last ounce of life from him for a dispassionate voyeur. Fated to answer for his Sisyphean boulder with his neck each time the film is projected, the least one can do is have some consideration for Tuco’s sufferance, such that, like for Jarman, some semblance of it is transformable within the context of our own pains. But Tscherkassky, as Tuco’s filmic captor, seems to express a bleaker perspective on the Sebastian-syndrome of pleasure derived from pain. Tuco experiences more pain than pleasure because his captors – the contemporary filmmaker and audience's lack of consideration – have managed to manipulate and articulate his surroundings according to their whim into a silo which he is unable to make sense of and therefore his resistance bears no trace of identity. The locus of power, so heavily concentrated by the mainstream or heteronormative (to use a Sebastian-appropriate metaphor) centre, plunges Tuco’s identity into a void where there exists no point of view through which his otherness is even comprehensible. Ultimately, the question is: Does Tuco suffer for nothing? His resistance has been curbed from transforming into a process or community, and therefore, his efforts mean nothing but siloed, chaotic strides to make sense of his identity. His resistance in life is unable to exceed the impositions of his captors in death, and therefore Tuco becomes a representational symbol of a more sombre martyr, one other’s will never know. He has been rendered a purely pornographic object, bound and penetrated for our sadistic, spectatorial pleasure. He becomes a mirror image of Sebastian, and we become Severus, finally able to quench our unrequited, lustful thirst.

Instructions attempts to turn the film inside out, often watching the film from the other side, i.e. from Tuco’s point of view, watching the audience from inside the screen. Delineating our inherent position of film watchers as that of a captor, and taking it a step further by exposing the tension between film and cinema – the material as captor of the content – the cinematic content strives to remind us of these positions we occupy. The cinematic content attempts to shine through its captivity in a light and sound machine to shake our passivity in violently undermining and discarding the misery and trauma of the many saints who suffer for us up there on the screen. Sebastiane, too, attempts a similar reversal of point of view. In classical representations, Sebastian is depicted in a passive position experiencing the pleasure of unity with the arrows stabbed. Sharing some kinship with the concepts of Instructions, David propounds, ‘Even if Sebastian’s tormentors are consigned to the repressed, out-of-frame space in most iconic representations of his suffering, as spectators to this scene, we are the ones in closest proximity to the position of the sadistic agents who have caused [it].’ So Jarman, subversively, heretically, flips the scene, ending his film with a fish-eye image looking over Sebastian’s tormentors, bows in hand, only, seemingly, not from Sebastian’s point of view – the camera isn’t pointed in the direction of his gaze to the heavens or the sun. Both these films, in their processes of reversal, desperately brandish tactics of getting one to grow aware of their inherent position as captor and eventually, hopefully, an acknowledgement of one’s captivity elsewhere in life, enabling one with the means and a prayer of somehow finding pleasure and faith in resistance. If we are the ones being tormented in a certain aspect of our lives, it's easier to blind ourselves to the pleasure we take in doing harm to others.

Tercan points out, ‘Queer theory acts to destroy the normative structure that is considered to be what is normal or natural in the binary structuring of the sex that is made dominant by the heteronormative imperative. Its purpose in questioning normality is not to strengthen the centre, but on the contrary, to build a disidentification policy by destroying the centre.’ Therefore, pleasure in suffering arises from not only the expression of an identity in the face of its repression by the dominant centre but also by the alignment of an otherness with similar others, creating a community that attacks the centre itself. Sebastian had Justin, another exiled soldier, acting as a sort of “queer brother’s keeper”, tending to Sebastian’s wounds and trying to understand his willingness to suffer. Who does Tuco have then, if not we the people out there in the dark? It's up to us to decide whether Tuco lives and dies for something. Tuco, like many screen Sisyphuses, runs the risk of having no community, and therefore we run the risk of misidentifying ourselves, for we exist simultaneously as captive to our captor, alone.

Brothers in captivity and suffering, though experienced separately, history has deemed Sebastian a Saint, and so too has cinema ordained Tuco, The Ugly.

2. The Narrative Devices of Aftersun [2022] and Three Questions About Fathers

PRAKHAR PATIDAR

The quiet revelation of one’s father’s personhood is perhaps the biggest rupture that marks the end of childhood. When you trace the cracks that led to it under the knowing light of hindsight, fathers become mere humans: flawed and often lost. When I saw the picture of my father as a young man, a vague disbelief took over me. I knew it was true. He was a lanky med student once, a sullen teen forced to continue education in a neighbouring town before that, a child swinging branches of guava trees in the farm earlier still. I just couldn’t believe it. He looked like a ghost of the man I know. The man who has been a father — good or bad — in a way that your child brain perceives as all he is, a complete picture, is also someone beyond that image and has been someone before it. This is why Charlotte Wells’ remarkable debut feature Aftersun [2022] sinks in so effortlessly even if one isn’t Sophie, a thirty-one-year-old new mom in Scotland who is stitching a trip she took to Turkey with her father, then thirty-one himself, with videos, memory, and imagination.

Using these three narrative devices, Wells offers a layered portrayal of the father-daughter dynamic that adult Sophie uncovers twenty years later. I use her excavation to address the three questions that have lingered since my first viewing of the film:

Have you seen your father cry?

The film begins with the non-diegetic sound of tape being rewound, and it opens to shoddy handycam footage of a happy and present Calum [Paul Mescal], a young father, as seen through the eyes of his eleven-year-old Sophie [Francesca Corio]. Perfectly cast in a film that demands raw performances, Mescal brings the unease of being a grown up contrasted with Corio effortless portrayal of the freeing unawareness of childhood. We know someone is looking back at this memory that has been bottled in a moving image. Through a quick reflection on screen, quickly followed by a cut to a dance floor flickering with club music and transient light, we learn it is Sophie, now almost as old as her dad in the video clip. In a direct visual representation of a time she is trying to recollect is a pixelated montage of a trip that occupies the majority of the film’s plot. Right here, Wells lays bare the film’s thematic core and form that molds it into a moving narrative where, though nothing much happens, Sophie reconstructs a “father she knew” to meet “the man she didn’t”.

In the videos from the trip, we meet Calum, the happy father. He dances to make her laugh. He teases, he smiles, he performs. In moments he knows will be preserved, he is who he wants to be remembered as. At night, after days washed in the warm, sunny blue of vacation stuff – lounging, swimming, sightseeing, eating fulfilling meals – once Sophie is asleep, he rewatches the day’s recordings, hunched over the footage like someone trying to make sense of it all. Somewhere in the middle of the film, we return to that opening in its entirety. This time, seen not as a joyful keepsake but as a faintly desperate performance. There’s a brief but piercing moment when Sophie, offhandedly, asks Calum, as an eleven-year-old, what he thought he'd be doing at thirty-one. There’s no answer, only a shift in tone. He can’t keep appearances anymore. And having met him in Sophie's memories, the viewers can see through it all.

Where do fathers go to cry?

In a pivotal scene, Sophie lies supine on the bed, speaking with the kind of loose, wandering honesty that children often possess. She rambles across the wall to Calum, who is just out of sight in the bathroom — a physical and emotional divide marking the separate worlds they inhabit. She tells him about a strange feeling she sometimes gets: a kind of tiredness that feels like sinking. He knows this feeling a little too well but doesn’t acknowledge it. Instead, he wraps it in silence to be found by adult Sophie when she comes back looking for all that was unspoken. He emphasises, ‘But we’re having a good time, eh?’ and then, in a jarring move, spits on his reflection.

The Calum of Sophie’s memories is a loving, struggling father. Earnest in his desire to give his daughter the best, and terrified that his battles — with depression, with money, with himself — will keep him from doing that. He brushes her hair and tells her, ‘You can be whoever you want to be. You got time.’ In Sophie's recollection, in the light of the opening scene (the video where he is asked about his aspirations at eleven) in his hopes for his daughter echo his failures. Twice in the film, Wells uses songs to pierce the emotional membrane of the moment. The first is the karaoke scene, when Calum can’t bring himself to sing. It’s a moment that calls for spontaneity, joy, performance — a literal and metaphorical demand of fatherhood. But he refuses, leaving Sophie awkwardly alone on stage singing R.E.M.'s “Losing My Religion”. ‘I think I thought I saw you try… but that was just a dream.’ The lyrics land like a diagnosis, and the evening spirals into a negligent night where Sophie is locked outside the room and a drunk Calum has fallen asleep naked in their room. What adds to the gnawing guilt he wakes up with is Sophie's grand gesture the following day. Framed on top of the stairs of the ruins they are visiting, while Sophie gets co-tourists to sing “For He's a Jolly Good Fellow” for his birthday, Calum is, for a moment, the father he wants to be. Superimposed is the image of him sobbing alone in a hotel room, having plummeted in guilt to the low he is desperately trying not to be.

How does one console a vulnerable father?

At the very end of the film, the second of the abovementioned surgical use of music, Sophie stands in a rave amidst a crowd in trance. Across the room is Calum, seemingly swaying to the music – David Bowie and Queen’s “Under Pressure”, a song that continues from the previous scene; another dance floor in Turkey: child Sophie and her father in a warm embrace. Here, in flashes of light synched to the beats, a synapse happens between her present and past. Across the room is Calum, swaying, visibly lost and in need of escape. Sophie makes her way to him and throws her arms around him, as if holding him from falling apart.

In her imagination, we meet a Calum she understands because she wears his shoes now. The tiredness that drowns one fills every space he occupies alone in her recollection of possibly the last time she met him. Surviving friends and family have often described the final moments with those who died by suicide as cheery, thoughtful, peaceful even. When one decides to leave, all there is left are goodbyes. In the film, when Calum is alone, he is either trying to hold on or preparing to let go. He meditates. He practices Tai Chi. He buys a rug he can’t afford, leaves Sophie a postcard asking her to never forget that he loves her very much. What do we do with the signs we only learn to read after it’s too late?

3. Cinema as Discomfort

VARUN OAK-BHAKAY

Should cinema entertain? Should it provoke? Be casual or serious? Leaving the theatre: smile on the face and nary a thought in the head or a frown and a few too many ideas which require at least a pint and a chaser to digest properly? There is obviously no one answer to this. It's the multifarious nature of the arts, their variety and individual quirks that makes them interesting. Nobody wants to listen to the same music day in, day out, or read the same kind of book. This is also a minority view, and as someone who doesn't engage with cinema for a living any more, I have grown to empathise with the majority a lot more, some of whom work tiring jobs and just want a rest at the end of the day. Their source of relaxation, given their exhaustion, has to be something which doesn't demand much of their mental faculties.

I understand that perspective but even with the things I look at every day, just a barrage of war and policy-related stuff, cinema remains one of the things I wish to be challenged by. Something that leaves me pondering for a while, something that needs to be considered over a Sunkist Lemon-n-Lime and a salted popcorn (both small; a major learning in the back half of my twenties is that some stuff is just too sugary and all portion sizes in the Western Hemisphere are better suited to a blonde American president).

Discomfort, in that respect, is comforting. It forces the brain to think of things it would much rather not confront. Books can be discomforting, often a lot more than cinema can be: an example is Vikram Seth’s doorstopper A Suitable Boy – I read it in 2020 and the quibble I had going through its pages was how little society in India appeared to have changed in the seven decades since the novel’s setting, that matters like untouchability and women’s rights were still being debated and discussed when they ought to have been resolved.

In Nora Fingscheidt’s The Outrun [2024], Saoirse Ronan played Rona, a young woman in the throes of research, living the good life in London, surrounded by friends and booze. The former thin out over time and Rona’s consumption of the latter escalates to concerning proportions. As someone with more than a passing fondness for alcohol, and a new arrival in London to boot, the film had me worried when I first caught it, coincidentally mere metres away from the venue where Ronan-headlined Blitz [Steve McQueen, 2024] was making its bow. Having survived the subsequent eight months with not one day wasted in clutching my head after getting wasted, I can now perhaps look back at the experience of absorbing Rona’s crumbling world as an exercise in misery. But in that particular situation, I was drawn to the film because of Ronan, one of the finest actors of her generation, not because I'd read the source material or screen depictions of alcohol were some kind of high for me.

When I walked into Shame [Steve McQueen, 2011], it was out of choice. I sought the film out because of what I'd heard of it. Sometimes you know all about a film even before you’ve watched a frame of it: I’m yet to watch It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World [Stanley Kramer, 1966] purely because my father, having heard me utter the title once years ago, had proceeded to tell me exactly what happens in the film. I knew exactly how Shame was likely to pan out, or at least had the beats of the film in mind going in. What I wasn’t as prepared for was how much I enjoyed it. Being neither a sex addict nor a pervert, I have to deduce that it was the filmmaking that was engrossing. The ideas that McQueen and lead actor Michael Fassbender were locating in the hellscape of New York City (sure, I’ve never been, but I’m more anti-big city than most people) and in Brandon’s [Fassbender] life, which doesn’t revolve around sex – which he treats with the dismissiveness of anyone who has forgotten the value of a good thing due to surplus supply – as much as it tends to turn it into the mundanity of everyday existence. It was this depressing quality of life that made the film interesting.

All around us, increasingly so since smartphones became a third limb and another essential organ, there are people who seek to monetise all the elements of their life. Where earlier one was encouraged to turn one’s passions into a government job (which has its pluses: a routine is particularly great; conversely, a lack of drive that one tends to associate with government, as well as the absence of accountability, mean a passion fashioned such will soon combust), the trend now is to turn every moment of our lives into some form of content and peddle it on every platform accessible to humankind. How does any of this tie into Shame? Well, just that we tend to romanticise the past, and a film released over a decade ago has no difficulty depicting how automated our lives had already become. That is the greatest of all discomforts, surely, not Margot Robbie appearing nude in a doorway in The Wolf of Wall Street [Martin Scorsese, 2013] while you watch the movie with a parent.

Much of why Shame works this way is because it strips away the cinematic allure of sex, which has often focussed on the “lovemaking” subsection. Rampant sex has long been the domain of the American Pie-and-Cousins franchises. McQueen reframes sex and sexuality in rather harsh frames, with something robotically industrial about the way all of it is lit. He gets rid of any suggestion around sex, consigning it to the corner where Brandon likely left his ability for rational thought. The character becomes an automaton through his sexual life, through the extreme detachment he approaches it with – ridding it of any and all intimacy to the point that an unplanned sexual encounter which he has not sought out deliberately goes south. Minutes after his partner has left, Brandon is shown going at it with a sex worker. His sense of emotional distance (which is core to the character’s interactions with his sister Sissy, played by Carey Mulligan) has damaged the fundamental ability to form an equation that goes beyond the quantifiable, to the end that it really doesn’t matter who he is having sex with, what their orientation or sex is, as long as he is having sex.

Amidst all of this, what is most dispiriting and thus valuable, is Brandon’s treatment of human interaction as some form of arch-consumerism. Shame could be interpreted as an indictment of the overt endorsement of purchasing power and ability that has plagued society for long. If everything is a consumer good, and that includes people, just what value is left in existing, one asks. For that is exactly what Brandon is doing: existing. Well, that and having rampant sex.

Picks of the Month

A short list of the writers each choosing the best film/show they’ve watched in the preceding month

Vanij: Loves of a Blonde (dir. Miloš Forman, 1965)

Prakhar: Challengers (dir Luca Guadagnino, 2024)

Varun: The Ballad of Wallis Island (dir. James Griffiths, 2025)

Call for Guest Contributors

Cut, And Print! emerged from the shared enthusiasm of a bunch of young film critics interested extending their habit of “living and breathing” cinema to “writing and publishing” about it. While our core team contributes to the Newsletter regularly, we are always on the lookout for people to join our tribe.

If you’re interested in contributing you can….