INTRODUCTION

A team shuffle and a crazy busy month later, here we are with another edition. This one’s a very reflective compilation of writings about cinema where

tries to write his way out of a writer’s block by writing about the block itself, revisits Michael Mann’s Heat [1995] to dissect ideas of masculinity and explores Asian modernity and the American dream through Edward Yang’s Taipei Story [1985]. Adding to the thread is the guest contributor Anand Verma writing about sons, distant fathers and The Mehta Boys [2025].1. Making Nothing Mean Something

VANIJ CHOKSI

Has anyone ever tried to write about writer's block while experiencing it? I have not yet had an idea I find worth exploring in this piece. I feel inert. Although why can’t that very feeling become the heart of the piece? That’s exactly what I’m thinking to myself as I write this. At this point, I'm not even looking up at my screen as I press down on the keys of my laptop. I've probably made plenty of spelling errors, but I’ll clean that up once this word vomit is out of my system. I think that a lingering version of my writer's block remains evident in my choice of language so far, for while writing this, I'm unable to find the words that describe my inability to find an idea. On one hand, this could turn out to be my most bland piece. On the other, in a way, it could serve to reflect my actuality as a writer uninhibited by the necessity of presentation. Is this what I actually am as a writer, that shines through the prose I employ? Is this where the basis of all ideas stem from, this raw, uncharacteristic state that simply is and eventually undergoes a process of adapting into a certain style of writing? There you go, I’ve had an idea. If you don't know what to write about, you write about not knowing what to write about. There is always something to write about!

Similarly, I've thought about this process in terms of filmmaking. If I encounter a filmmaker's version of writer's block and cannot see a possible idea to explore filmically, can I not make a film about just that? Just like this piece reads, the film too would contain no aesthetic additives for its sake, rather bringing attention to my experience of time, sitting alone in a room simply thinking. In a way, a durational shot of someone thinking in a room perhaps prompts thought within an audience's mind. Therefore, can it not be that this is when the power of cinema is at its highest: creating an experience for an inert audience that is being experienced truthfully by the filmed subject? We’re both now locked in thought, staring at each other, wondering if the other sees us. Looking at somebody looking at nothing, over time, dissolves into a nothingness in observation on our part as well. Now we’re connected. I understand you. Are you able to understand me?

If I am able to achieve that with a singular, solitary, durational shot, would it not be the logical next step to attempt to expand that experience over the length of a film? What would that film look like? Nobody wants to merely look at someone look for the better part of two hours, but in creating a state of “looking” – of critical observation – I feel like I can extend that meditative state into the observation of other things. I can shift focus to seemingly banal objects and moments and my audience's observant logic will carry through. An elevated method of looking has now been offered by the filmmaker and accepted by the audience. In its reciprocation we become one, co-authoring the meaning of what we’re subject to. These seemingly banal objects and moments, however, do not exist as an experiment in observation, it doesn't come from the want to “search” for meaning. Cinema is not a science experiment, it has meaning that is poured into it by an author, yet its experience can be as multifaceted as there are people with perspectives. The film image then, I conceive, is the depiction of something so literal that it exists as it is, yet its experience has an air of ambiguity that fires in directions infinitely more vast than the seeming finiteness of the image. It has heart.

It takes risking banality to achieve something profound. I feel like writing this piece makes that make sense to me.

2. Men in Heat

VARUN OAK-BHAKAY

Of the one hundred and twenty-six films I watched during the extended Coronavirus lockdown of 2020, Michael Mann’s Heat [1995] was the fifth. It ranked seventh on my top ten watches of that period. As an almost graduate, I found Heat extremely cool. A pulsating rhythm ran through its hundred-and-seventy-minute runtime. The action set-piece outside the bank was riveting for both its cinematic prowess and for how Mann amplified the tools available to him to evoke a particular response from the audience. While I was not cinema-literate enough to appreciate the coming together of Robert De Niro and Al Pacino, I’d watched enough mainstream Hindi cinema growing up to know what a treat their confrontation would have been for audiences of the Nineties. I have revisited Heat a couple of times since, and on the more recent of those occasions, when I caught it on a Monday afternoon in a packed theatre as part of its thirtieth anniversary showings, I came away admiring something about it that is almost central to the film.

Every single thing about Heat screams masculinity. It’s bathed in bold, dark hues that are monotonous but stylistically rich and mostly associated with men, it features high-speed getaways and booming gunfire echoing in the cityscape of downtown Los Angeles, the women are on the fringes of the narrative, and it’s really about two men doing “manly” stuff like robbing banks and whatever it is police officers do. What is of interest to me, however, is that the film is actually about the failures of these men in a more everyday sense; no matter how masculine their appearances may render them, they fail, catastrophically, to be real men. What’s Mann’s idea of manliness, then? Does his film even address it in any way, shape or form, or am I just reading too much into it?

Growing up in a Fauji (Hindustani for “military”) household, my ideas of masculinity were non-existent. Much as that statement sounds like an oxymoron, it holds true for my memories of my childhood. Unlike what people believe, professional soldiers do not keep weapons about the house (though I do know how to shoot, and decently so, as evidenced by my performance in two fairs recently, which netted me a stuffed gingerbread man and a stuffed penguin). Our father did not expect military discipline out of my sister or me – we called him “Papa” (and not “Sir”, which is something a lot of people thought) and did not accompany him to physical training or the drill square (come to think of it, I don’t think anybody not in training or not practising for a parade winds up on a drill square). My childhood was not punctuated by gendered activities and so masculinity as a concept was something for the movies, and even on the silver screen, guys like John Abraham had long (read “girly”) hair so just what were the reference points? I ended up basing my concept of “being a man” on the specimens of the human males I saw around me: attributes like working hard, being responsible, having a neat haircut with the sides and back shorn short. Bear in mind that these are equally applicable to women and to other genders, but because I identify as a man, and those who considered themselves men when I was a kid were like this, this is what I presumed the ideal man had to be like.

Cut to Heat, in which Vincent fails the haircut test and is as irresponsible as the man he is tracking. I find it useful to separate their professional capabilities from the people they are, since work is one among many of life's undertakings. And while it's true that Heat could be read as a film that is essentially about consummate professionals and the all-consuming nature of their chosen vocations, the function of their maleness within the narrative is integral to understanding both Neil and Vincent. There are certain things Mann doesn't bother exploring, like the colours they wear and the cars they drive. He shapes the film around their fixated natures and what that tells us about them as men. He chooses to explore why they fail as romantic partners but are less of a failure to their adoptive children (quasi-adopted, in the case of Neil’s relationship with Chris Sheherlis, played by Val Kilmer).

Neither Neil nor Vincent starts out as the ideal human male. They aren't expected to be. They are both understood to be in control of certain aspects of their lives and juggling the other — Vincent’s marriage is falling apart and Neil needs to be on the lookout for the next score whilst grappling with emotions he's never considered important before. As leaders of their respective outfits, they are sources of authority. With their sharply-tailored suits and slick weaponry, they are kitted out to be conventional males of their time.

Neil, who has always lived by the dictum of not tying oneself down to anything which cannot be jettisoned when the heat is round the corner, loses his heart to a designer despite himself. Vincent, meanwhile, is unable to commit to the requirements a marriage requires of him. Neither of these are failures in any sense; the inability to stick to their guns is. In the end, Neil and Vincent are left with just one another for company before Mann cuts to black. The melancholy of the scene comes not from the death that occurs but how it is the consequences of the choices made earlier in the day, and from the failures along the way.

3. What Do You Mean America Is Not the Answer?

Asian modernity and the American Dream in Edward Yang’s Taipei Story (1985)

PRAKHAR PATIDAR

‘Europe mein kya hai?! Aap America jao!’ (‘What does Europe have to offer? You should go to America!’)

This earnest advice came from a man whose son was preparing for college admissions. This was my first job, I was working on my own doctoral applications to European universities on the side. With a literature degree and what they call “academic rigour”. In the college counselling world, that turns you into an academic/writing coach (read: ghostwriter) and the next thing is you’re meeting parents and their mostly clueless children, trying to align their hopes and aspirations into a college essay. The fact I was in the same process, albeit a few years ahead for a more advanced degree, made for the go-to icebreaker.

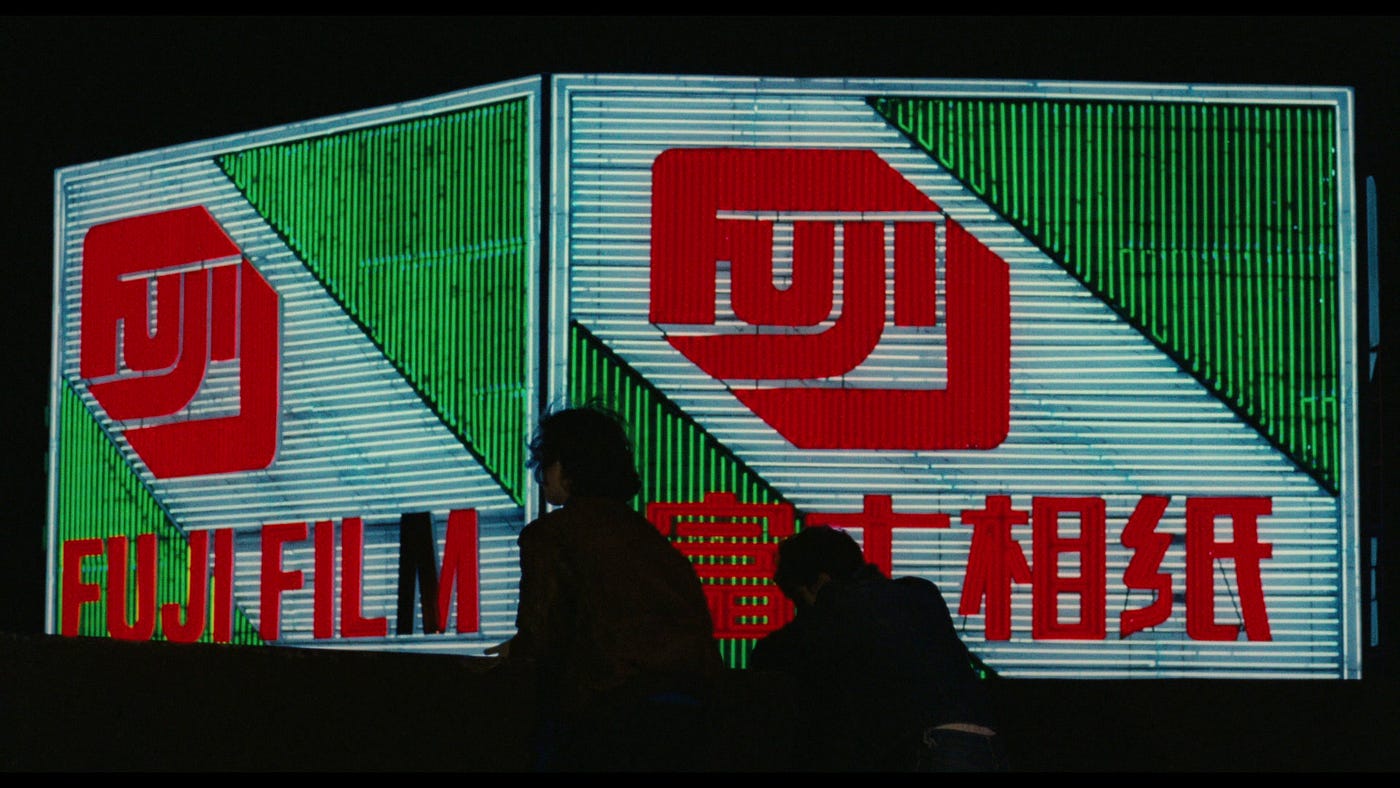

I grew up on a steady diet of American cinema — enough that it hijacked my ideas of what was “cool”, “better”, and “modern” for much of my teenage years. A second-hand patriotism for all things American, if you will. And now, at the cusp of my late twenties, I found myself eerily at home in Edward Yang’s Taipei Story [1985] — a realist tragedy about a couple quietly growing apart. Cheng [Tsai Chin], a career-oriented woman enchanted by the distant dream of immigration, and Lung [Hou Hsiao-hsien], a nostalgic man disillusioned by America after a recent visit.

Before making films, Yang was a software engineer in Seattle and had been offered a place at Harvard to study architecture. He returned to Taipei at thirty, where he began crafting a cinema defined by technical precision, neorealist leanings, and a striking command of storytelling through space — all of which helped define the Taiwanese New Wave of the 1980s and ’90s. Like India’s own Parallel movement from the ’60s to the ’80s, these were films that challenged the mainstream — reflective, restrained, and deeply political. More than anything, the New Wave was about Taiwan in flux. The ringleader of this cohort of restless men reinventing cinema, Yang distilled the movement’s themes into Taipei Story, co-written with Hou Hsiao-hsien (who also stars as Lung). The film is a tender unravelling of a relationship between childhood sweethearts who are no longer on the same path — if they ever were. Possibly in their late twenties, Cheng and Lung represent a city moving too fast to hold onto its roots. They look in opposite directions for answers — one to the future, one to the past — and lose one another in the process.

[Minor spoiler]

Films that open with a new home are rarely happy ones. Think of the whole haunted house genre [The Amityville Horror (1979, 2005), Paranormal Activity (2007), Sinister (2012), Vivarium (2019)] or the unravelling relationships horror [Les Créatures (1966), Revolutionary Road (2008)]. In the opening scene, the couple — already bereft of any warmth associated with new love — tour the apartment Cheng is about to rent. This is a move away from the confining roof of her traditional father who suffers from a classic condition of everyday chauvinism and an acquiescent mother Cheng refuses to turn into. Lung comments on the practical aspects of the work the palace will need to be livable, in a visual style defining, geometric frame they stare longingly out the window in silence, the apartment turns into their house as the opening credits roll, the warmth of a lived-in home is nowhere to be found and the tone of the film is set.

The past peels away like old wallpaper, evident in the spaces Yang places Lung to construct the character’s interiority — Cheng’s childhood home, her father’s tales of a simpler times, memories of his days as a baseball little league champion, playgrounds with an ex-lover, old buildings enroute ruin. The future arrives swiftly — in glass buildings and imported dreams, in the vast emptiness of modernity that tugs at Cheng, reminding her that reminding her much of it to be wanted, earned and done. There’s the American Dream, and then there’s the Asian version of it. The original was farcical, simple: work hard, stay honest, and you’ll rise — into a home, a career, a perfect picket fence family life. It promised not just comfort, but arrival. Its Asian counterpart, especially in postcolonial or newly industrial nations like Taiwan, carried the same ambition but twice the weight, less about freedom and more about catching up. The dream didn’t arrive organically — it was imported, like the mechanical Pepsi can toy Lung brings back.

When Cheng loses her job and is left more unsure than before, she takes temporary solace in the carefree tempo of modern youth via her younger sister. A kind of youth that isn’t burdened with trying to live a life that bridges generations. The kind that has unlocked a new way of being young not earlier available to Cheng even though they practically belong to the same generations. The American coming-of-age high school films that I grew up watching and still keep up with for guilty pleasure have remained the same at the core, despite the setting, time or POV, there’s a quintessential way of being young marked by degrees, agency and freedom, an experience shared across generations. The past few years, of being eighteen once, having seen my sister navigate young adulthood and having worked with kids about to turn eighteen, feels like a decade of dizzying shifts. There is no continuing, slowly evolving experience of agency and freedom to be shared — there was barely any, suddenly some and then a little too much.

Caught in this flux, Cheng moves toward unfamiliar encounters — a married man at work, her sister’s impulsive friend — not for love, but for movement, for something that reminds her she’s still alive. Lung, meanwhile, reaches back to an old flame, back to what he knows, what is comfortable. Yang’s gaze rarely intrudes. It watches people walk away, linger at thresholds, leave doors half-open. No one says the things they most need to say. Instead, they turn their backs, move into other rooms, let silences stand in for sentences. Taipei Story is about a relationship coming apart, yes. But more than that, it’s about a country that can no longer fit itself into its old skin. About people who were promised a future they no longer recognise.

When I asked the man, “Why America?”, “Why not? It’s the best country in the world”, he answered.

GUEST CONTRIBUTION

4. The Mehta Boys and the Beautiful Decay of a Father-Son Bond

ANAND VERMA

"Father" is a hard-to-imagine word for me—a word that exists in my life but has been reduced to a blur. I have a fifty-one-year-old father, but to make things easier for myself and sound less accusatory, I will refer to him as Brendon. Even though Brendon and I are both in the living room, our shared reality feels blurred. Unfortunately, my relationship with him has always been a downward spiral, crossing many levels of anguish and agony. I notice some movement in the day-to-day domestic thriller that is our home, but at some point, I know it will become too reliant on the supplemental oxygen of weekend calls and hollow banter on WhatsApp. The movement is somewhat contrived yet frighteningly real. I have known Brendon for more than two decades, and he simply never embraced "father time" with his children. We were left bereft of his warmth, of the soft, nap-time-like presence a father might offer. He used to leave for the office before we woke up for school and return home long after we were asleep. Sundays were no exception. Perhaps, at some point, even an abnormally small amount of affection would have sufficed, but Brendon never induced even a flicker of longing for it.

The Mehta Boys opens with Amay Mehta [Avinash Tiwary], an architect living alone in a ceiling-leaking and paint-peeling-from-the-wall Mumbai flat. Despite his surroundings, he carries an elegant persona — one that makes his colleagues chuckle spontaneously at the office and earns him excessive care from his boss. It’s clear that he loves his job, and his girlfriend Zara [Shreya Chaudhry] pushes him beyond his limits for an ambitious project. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, a note arrives, leaving him in utter disbelief. What follows is a remarkably intense and tender film that struck a deep, familiar chord in me. The picture that emerges from the heart comes full circle under the tyranny of my current ambiguity. To say that I developed an affection for the film — what does that really mean? The Mehta Boys is something a little beyond the ordinary.

Boman Irani navigates a poignant and beautifully layered tale of a father and son, both trapped in an optical illusion of their own making until the sudden demise of Amay’s mother pulls him back to his grieving father Shiv [Irani]. At first, the conflict between the father and son in the film might seem like a singular forced separation, but it actually stems mainly from years of unresolved conflicts, emotional detachment, and unexpressed grievances. The reason Amay feels unloved and undervalued despite his accomplishments is that their relationship is characterised by awkwardness, miscommunication, and a failure to communicate openly, leaving both men confined within their emotional barriers and unable to reveal their vulnerabilities. Sounds similar, right? Like any other urban middle-class family, certain household rituals take precedence over raw emotions. For Brendon, ensuring that footwear is removed before entering the bier is more pressing than the challenge of holding back tears for a departed parent. Amay moves through the house quietly, avoiding confrontation with his distant father, yet sharing a deep closeness with his fiery sister. In one of their conversations, Amay quips, ‘If I tell him to breathe, he’ll hold his breath till he dies.’

Perhaps making the son fluent in the cosmetic language of architecture is intentional. All the goodness and heroism that can be summoned to create epic structures cannot, ironically, map out the intricacies of a decaying bond. Perhaps, too, the choice of the title — typewriter-punched Mehta and computer-key-pressed Boys — is deliberate, subtly anchoring the story’s essence from the very beginning. After all, the subjectivity of attention shapes the objective experience of the film. Just as cultures and inventions enjoy their epoch before evolving, some relationships feel like old thoughts reborn into new moments.

In my mind, I am unable to fantasize about sharing an elevator with Brendon or being in any confined space with just the two of us. Throughout my life, I have avoided — or, to be more precise, struggled with — staying in the same space as him. Whenever we happened to be home alone while my mother was at work, I would usually slip into another room to escape the cold loneliness of unnurtured conditioning. This is not only an amusing signpost for incompatibility but also a missed opportunity to reflect on differing perspectives and foster mutual understanding.

This is why the elevator scene in the film, or the idea of having drinks and pakoras with your father — chiseling out priorities and debating whose job was better, becoming a shoulder to rest on — felt like an uphill battle for me. Irani’s portrayal of an uncomfortable yet rewarding father-son relationship hit home. His craft, if you really dig deeper, is essentially assuring. Irani compels Shiv to be pragmatic before his son, yet frightfully vulnerable before the visions of his late wife, and charming before his would-be daughter-in-law. All of these shifts, these forces, exist within a single film.

There is a moment when Shiv, on the day he is set to leave the home he has spent his entire life in, anxiously types out his will. His daughter, rightfully pleading with him to stop, insists they wait until they get ‘home.’ To this, Shiv erupts, "This is home." He lets his angst lash out.

The women in the film are in a delightful role — they are quite a revelation. At its core, they unwittingly illuminate the broken flashlight of a fractured relationship. And in doing so, the boys — Amay and Shiv — come to understand how unfair they have been to each other over the years. So, in the final act, when Amay switches off the corridor light, it becomes a testament to the quiet surrender of past grudges.

While writing this, I found myself reflecting on my struggling relationship with Brendon. I can picture him tending to the lawn’s plants during his Sunday downtime or watching cricket. I can imagine him, after much deliberation, asking my mother to call and check on me—his Amay, who is also managing his ambitions while living alone. Perhaps this is the film I would one day make Brendon watch — though even the thought of it feels unnerving.

Picks of the Month

A short list of the writers each choosing the best film/show they’ve watched in the preceding month

Vanij: Something Different (dir. Věra Chytilová, 1963)

Varun: Black Bag (dir. Steven Soderbergh, 2025)

Prakhar: Marching in the Dark (dir. Kinshuk Surjan, 2024)

Call for Guest Contributors

Cut, And Print! emerged from the shared enthusiasm of a bunch of young film critics interested extending their habit of “living and breathing” cinema to “writing and publishing” about it. While our core team contributes to the Newsletter regularly, we are always on the lookout for people to join our tribe.

If you’re interested in contributing you can -